HVAC systems function as active thermal energy transporters, overcoming natural entropy to maintain specific environmental states. Operation is dictated by the Second Law of Thermodynamics: heat naturally migrates toward lower energy states. Reversing this flow—extracting thermal energy from a cool interior and rejecting it to a warmer exterior—requires mechanical work within a closed-loop refrigeration cycle.

System efficacy relies on the manipulation of latent heat. By controlling the pressure-temperature relationship of a refrigerant, the system creates the thermal gradients necessary to facilitate heat exchange against natural environmental flows.

Contact for upgrading your Facility for Schedule-M

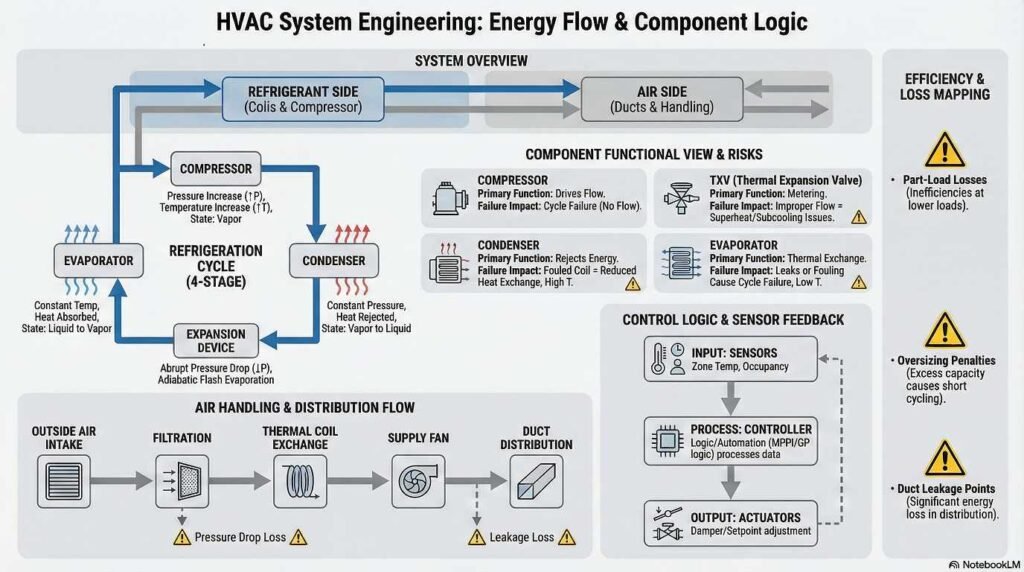

The Vapor-Compression Cycle: System-Level Logic

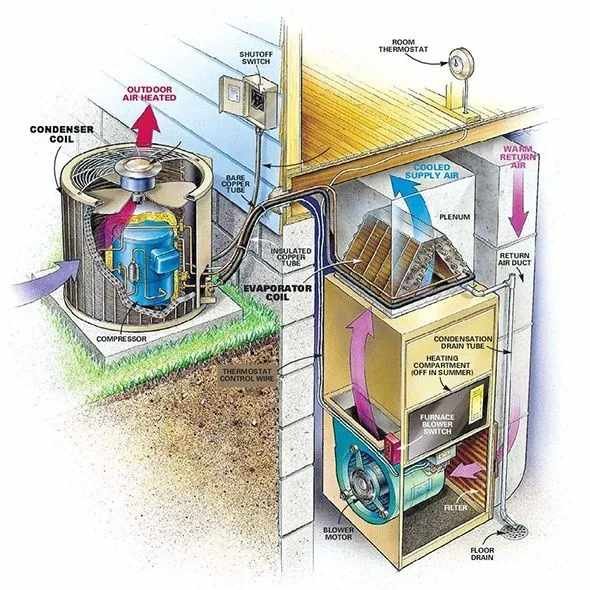

The vapor-compression cycle serves as the mechanical engine for heat transfer. It consists of four distinct stages where the refrigerant’s physical state is altered to move energy between the air side (indoor environment) and the refrigerant side (heat sink/source).

Shutterstock

1. Compression (Mechanical Energy Input)

The compressor draws in low-pressure, low-temperature vapor. Applied mechanical work increases vapor pressure and elevates its boiling point. This results in a high-pressure, superheated vapor with a temperature exceeding the outside ambient air, establishing the gradient required for heat rejection.

2. Condensation (Exothermic Heat Rejection)

In the condenser, superheated vapor releases thermal energy to the external environment. As heat dissipates, the refrigerant undergoes a phase change from vapor to high-pressure liquid. Efficiency depends on the delta between the refrigerant temperature and the external medium (air or water).

3. Expansion (Adiabatic Pressure Modulation)

The high-pressure liquid passes through an expansion valve or metering device. This imposes a sudden pressure drop, causing a portion of the refrigerant to “flash” into a gas. This adiabatic process rapidly cools the remaining liquid-vapor mixture, preparing it to absorb indoor thermal energy.

4. Evaporation (Endothermic Heat Absorption)

Cold refrigerant enters the evaporator coil. As indoor air passes over the coils, the refrigerant absorbs latent heat and evaporates into a low-pressure vapor. This removes thermal energy from the air side, lowering the temperature of the conditioned space before the vapor returns to the compressor.

Functional Component Interactions

System performance is defined by the synchronization of mechanical components and the thermophysical properties of the refrigerant.

Compressor Architectures

- Reciprocating and Scroll: Utilize positive displacement. Scroll compressors are standard for residential and light commercial applications due to higher efficiency and fewer moving parts.

- Centrifugal: Utilized in high-capacity chillers. These require precise management to prevent “surge”—a flow reversal caused by high head pressure that can lead to mechanical failure.

- Screw: Employs twin rotors for continuous compression in medium-to-large-scale applications.

Refrigerant Evolution and Regulations

The refrigerant is the primary medium of energy transport. Selection is driven by the AIM Act and EPA regulations, which mandate the phase-down of high Global Warming Potential (GWP) Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). Focus has shifted toward substances offering optimal thermophysical properties while meeting environmental compliance.

Control Logic and System Interoperability

Systems have transitioned from reactive thermostatic control to integrated building automation and predictive modeling.

Communication Protocols: BACnet vs. LonWorks

Interoperability between multi-vendor components is achieved through standardized protocols. BACnet (ANSI/ASHRAE) is the dominant standard for large-scale integration, utilizing existing LAN infrastructure for robust internetworking. LonWorks remains an alternative, though BACnet is generally preferred for scalable, high-performance building automation.

Advanced Automation: Uncertainty-Aware Control

Emerging systems utilize Model-Based Reinforcement Learning (MBRL), such as the CLUE system. These use Gaussian Processes to model building dynamics with “uncertainty awareness.” By evaluating potential action trajectories, the system optimizes for energy efficiency and human comfort simultaneously, even with sparse or unpredictable sensor data.

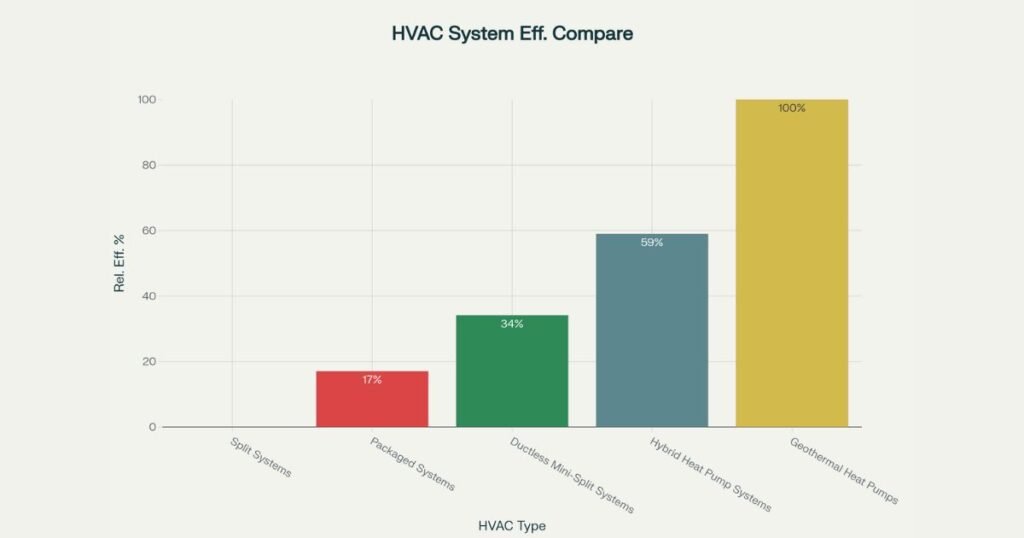

System Architectures: VAV vs. VRF

Architectural configuration dictates energy distribution efficiency.

- Variable Air Volume (VAV): Maintains constant air temperature while varying airflow volume. In many commercial applications, VAV systems require “reheat” cycles to prevent over-cooling, which can lead to significant energy waste.

- Variable Refrigerant Flow (VRF): Varies refrigerant flow directly to multiple indoor evaporators. VRF facilitates heat recovery—transferring excess thermal energy from one zone to another without engaging the primary heat rejection cycle—making it highly efficient for multi-zone buildings.

Real-World Performance vs. Rated Efficiency

There is a persistent gap between a system’s rated efficiency (SEER/EER) and actual operating performance.

The Economizer Reliability Gap

Air-side economizers provide “free cooling” using outside air. Research indicates standard economizers often achieve only one-third of potential savings. Failure points include seized dampers, incorrect changeover setpoints, and poor field commissioning. “Premium economizers” address these through more rigorous control requirements.

Heat Pump Barriers

Despite high theoretical efficiency, heat pumps face adoption hurdles including high upfront capital costs and technical misconceptions. Users often report heat pumps “blow different” than gas furnaces because discharge air temperatures are lower, despite the total heat delivered meeting comfort requirements.

IAQ and Ventilation Standards

Design must satisfy ASHRAE Standard 62.1 to ensure Indoor Air Quality (IAQ) without excessive energy penalties.

- Ventilation Rate Procedure (VRP): A prescriptive method setting intake rates based on occupancy and floor area.

- Indoor Air Quality Procedure (IAQP): A performance-based approach. It allows for reduced outdoor air intake if air cleaning technologies maintain specific design limits for contaminants, optimizing the energy required to condition outside air.

What regular maintenance does an HVAC system require for optimal performance?

Regular HVAC systems maintenance includes replacing air filters every 1–3 months, inspecting and cleaning ducts, checking thermostat settings, ensuring the outdoor unit is free of debris, and scheduling professional service at least once a year. Preventive maintenance helps extend system life, ensures energy efficiency, and reduces the likelihood of unexpected breakdowns

How do you determine the right size HVAC system for a building?

The appropriate HVAC system size is determined through a load calculation that considers the building’s square footage, insulation, window types, orientation, and occupancy. Proper sizing ensures the system operates efficiently—units that are too large waste energy, while units that are too small struggle to maintain comfortable temperatures

What is a SEER rating, and why is it important?

SEER (Seasonal Energy Efficiency Ratio) rates the efficiency of air conditioning systems. A higher SEER means better energy efficiency and lower operating costs. When selecting new HVAC equipment, choosing a system with a high SEER rating can significantly reduce energy bills and environmental impact over time

What are the most common causes of reduced HVAC systems efficiency?

Poor maintenance (such as dirty filters), ductwork leaks, outdated equipment, improper thermostat settings, and lack of regular servicing can all reduce system efficiency. Addressing these issues—especially through regular maintenance and occasional professional checkups—can help restore and maintain energy efficiency

What new technologies are improving HVAC systems today?

Recent HVAC innovations include smart thermostats, IoT-based monitoring, building automation systems, use of eco-friendly refrigerants, and variable speed drives. These advancements lead to greater energy efficiency, improved comfort, easier diagnostics, and reduced environmental impact.

References:

- ACEEE (Hart, R., Morehouse, D., & Price, W., 2004). The Premium Economizer: An Idea Whose Time Has Come. American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy.

- ASHRAE / PolarSoft (Fisher, D., 1996). BACnet™ and LonWorks®: A White Paper.

- Ding, X., An, Z., Rathee, A., & Du, W. (2023). A Safe and Data-efficient Model-based Reinforcement Learning System for HVAC Control. arXiv / IEEE.

- IBPSA Publications (Kim, D., Cox, S. J., Cho, H., & Im, P., 2016). Evaluation of Energy Saving Potential of Variable Refrigerant Flow (VRF) Systems Compared with Variable Air Volume (VAV) Systems in the U.S. Climate Locations. The 3rd Asia Conference of International Building Performance Simulation Association.

- Trane Technologies (2024). Compliance with the Indoor Air Quality Procedure of ASHRAE® Standard 62.1. Engineers Newsletter (IAQ-WPR001A-EN).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (2025). Background on HFCs and the AIM Act.

- Wikipedia. Refrigerant. [Technical Definition and Regulatory History].

- Wikipedia. Vapor-compression refrigeration. [Thermodynamic Cycle and Component Analysis].

- r/hvacadvice (Reddit). If heat pumps are so incredible, why are they not more common? [Market Adoption and User Perception Analysis].