Prior authorization (PA), also known as preauthorization or precertification, is a critical process in the United States healthcare system. It requires your doctor or healthcare provider to get approval from your health insurance plan before certain medical services, procedures, or prescription drugs can be administered.

Without this advance approval, your health plan may not cover the cost of the treatment or medication. Essentially, PA acts as a “green light” from the insurer, confirming their commitment to reimburse the costs. This mechanism helps health plans control costs by ensuring a specific service qualifies for payment coverage. It’s important to note that emergency care is typically exempt from this requirement.

Why Understanding Prior Authorization Matters for You

While prior authorization is designed to manage healthcare costs and promote appropriate care, its practical application often creates significant challenges for patients. These challenges can include substantial delays in receiving necessary treatment, considerable administrative burdens for healthcare providers, and, in some instances, patients abandoning their prescribed care altogether.

For example, studies show that 94% of patients experience care delays due to prior authorization, with 78% reporting treatment abandonment. Furthermore, 88% of physicians characterize the administrative burdens from this process as high or extremely high. Understanding this intricate process empowers you to better advocate for your care, anticipate potential hurdles, and navigate the system more effectively, ultimately striving to ensure you receive the care you need in a timely manner.

Why Do Insurance Companies Require Prior Authorization?

Cost Control and Resource Allocation

Prior authorization serves as a primary mechanism for health plans to manage expenditures and foster cost-effective care delivery. By requiring advance approval, this process helps to prevent unnecessary or inappropriate treatments, tests, or procedures. This ensures that healthcare resources are utilized effectively and efficiently.

This often involves encouraging the use of equally effective, yet more affordable, alternatives, such as generic medications, before approving more expensive brand-name options. For instance, PA can be instrumental for branded specialty products, ensuring they are reserved for patients who do not benefit from generic or non-specialty therapies.

Ensuring Medical Necessity and Quality Care

Health plans use prior authorization to assess whether a proposed service or medication is “medically necessary.” This means evaluating if the care is genuinely required to diagnose or treat an illness, meets accepted standards of medicine, and aligns with the latest clinical guidelines.

The process also aims to enhance patient safety by reviewing procedures and drugs for potential negative interactions with existing medications or their appropriateness for a patient’s specific condition. A significant application of prior authorization has been in controlling access to potentially addictive medications, such as opioids, where it has proven beneficial in managing access and reducing misuse, particularly since the height of the opioid crisis.

Fraud Prevention and Coverage Verification

Prior authorization plays a role in preventing healthcare fraud by verifying the medical necessity of requested services, thereby reducing the likelihood of unnecessary or fraudulent billing. Furthermore, it acts as a crucial check to confirm that the proposed care is indeed covered by a patient’s specific health plan.

This verification helps to minimize the risk of unexpected out-of-pocket costs for the patient, ensuring clarity regarding their financial responsibilities. While the initial goals for prior authorization are rooted in ensuring “medical necessity” and “cost-effectiveness,” its application has expanded considerably. It now frequently encompasses generic medications and even requires re-authorization for ongoing treatments. This broadening scope means PA is increasingly used as a pervasive gatekeeping function across a wider spectrum of care, which can lead to increased administrative burdens for patients and providers.

Common Healthcare Services and Medications Requiring Prior Authorization

General Categories of Services

While specific requirements vary by insurer and health plan, prior authorization is generally mandated for more costly, complex, or specialized treatments. Common categories that frequently necessitate prior authorization include:

- High-cost imaging: Such as Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRIs) or Computed Tomography (CT scans).

- Surgeries or invasive procedures: Any procedure considered significant or complex.

- Specialty medications: Particularly branded products where more cost-effective generic alternatives might exist, or those reserved for specific patient conditions.

- Some durable medical equipment (DME): Items like wheelchairs, oxygen tanks, or sleep apnea machines.

- Behavioral health services: Although some states are actively working to ban prior authorization for certain behavioral health treatments due to parity violations.

Medications Requiring Prior Authorization

Prior authorization is often required for medications with a high potential for misuse or inappropriate use, such as certain opioids. It may also apply to drugs with common interactions or complications, or those deemed cosmetic by the insurer. Medications not on the plan’s formulary or prescribed for off-label indications may also require additional justification.

Specific examples of drugs that may require prior authorization from some insurers include tralokinumab-ldrm (Adbry), acalabrutinib (Calquence), naltrexone bupropion (Contrave), and methoxy polyethylene glycol-epoetin beta (Mircera). Even the specific form of a medication can influence requirements; for instance, aripiprazole tablets with a sensor (Abilify Mycite) may require PA, while aripiprazole tablets without the sensor (Abilify) may not.

It is also important to recognize that even continuing a current treatment may necessitate prior authorization to confirm its ongoing benefit. While Original Medicare Part A and B generally do not require PA, Medicare Advantage and Medicare Part D prescription drug plans frequently do.

A common experience for many patients is discovering that prior authorization is required only at the pharmacy counter when their prescription is rejected. While insurers maintain lists of drugs and services that require prior authorization, this information is not always proactively or clearly communicated to patients. The primary responsibility for checking PA requirements typically falls on the healthcare provider. When a provider misses this crucial step, the patient is often caught off guard, leading to immediate frustration and delays in accessing needed care.

Table 1: Common Services & Medications Often Requiring Prior Authorization

| Category of Service/Medication | Examples & Key Considerations |

| High-Cost Imaging | MRIs, CT scans, PET scans. Often required to ensure medical necessity before expensive diagnostic procedures. |

| Surgeries & Invasive Procedures | Orthopedic surgeries, complex cardiac procedures, elective surgeries. Generally required for any significant or complex intervention. |

| Specialty Medications | Biologics for autoimmune diseases, certain cancer drugs, medications for rare conditions. Often expensive and may have specific usage criteria. |

| Durable Medical Equipment (DME) | Wheelchairs, oxygen tanks, sleep apnea machines, prosthetics. Ensures the equipment is medically necessary and appropriate for long-term use. |

| Behavioral Health Services | Certain types of therapy, inpatient mental health admissions, specific psychiatric medications. While some states are banning PA for certain behavioral health treatments, it remains common. |

| Medications with Misuse Potential | Opioids, certain controlled substances. Used to manage access and reduce misuse, ensuring patient safety. |

| Brand-Name Drugs with Generic Alternatives | Insurers may require trying a less expensive generic first if it’s equally effective. |

| Medications with Common Drug Interactions/Complications | Drugs that pose higher risks when combined with other medications or have significant side effects. |

| Medications for Off-Label Indications | Drugs prescribed for uses not approved by the FDA. Requires documentation of medical necessity and supporting evidence. |

| Ongoing Treatments | Continuation of certain services or medications. May require re-authorization to confirm continued benefit. |

| Specific Drug Forms | The same drug may require PA in one form (e.g., dermal patch) but not another (e.g., tablet). Example: Aripiprazole with/without sensor. |

Important Note for Patients: Specific prior authorization requirements vary significantly by individual health plan and insurer. Always consult your plan documents or contact your insurer directly for the most accurate information regarding your coverage.

The Prior Authorization Process:

Who Initiates the Request?

The responsibility for initiating the prior authorization process typically rests with the healthcare provider—specifically, the doctor or their administrative staff. It is their role to determine that a specific service or medication is medically necessary for a patient and then to ascertain if prior authorization is required by the patient’s health plan.

While the provider usually submits the formal request, patients can, in some circumstances, initiate the process directly with their insurer. However, the necessary clinical information and justification must still be provided by the patient’s doctor. To avoid duplication of effort or potential errors that could delay care, it is generally advisable for patients to coordinate closely with their healthcare provider throughout this process.

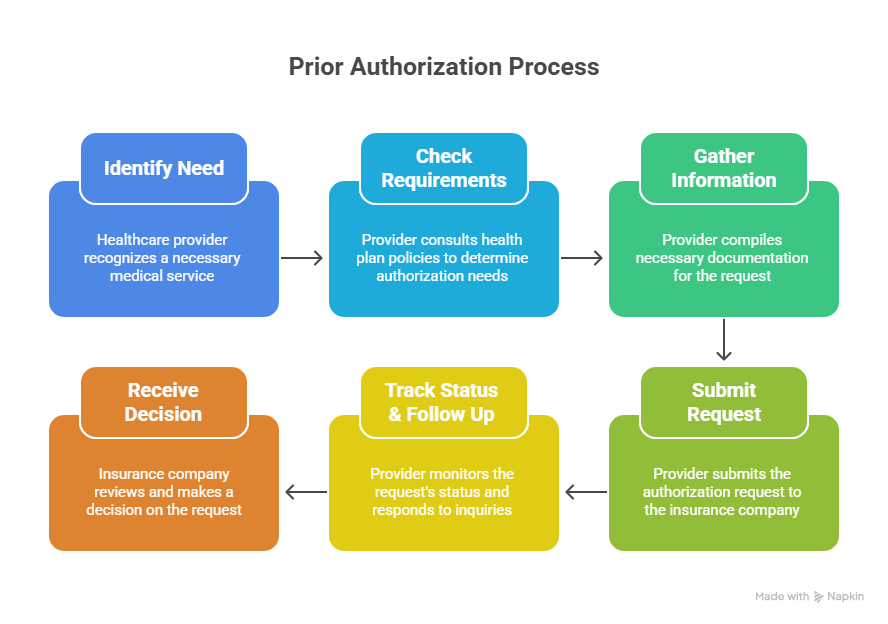

The Step-by-Step Process

The prior authorization process typically unfolds through a series of structured steps:

- Step 1: Identify Need

- The healthcare provider first identifies that a specific procedure, test, medication, or medical device is necessary for the patient’s care plan.

- Step 2: Check Requirements

- The provider’s office then consults the patient’s health plan’s policy rules or formulary to determine if prior authorization is required for the prescribed course of treatment.

- Step 3: Gather Information

- Once prior authorization is identified as necessary, the provider’s office meticulously compiles all required documentation. This typically includes patient identifying information, insurance ID, diagnosis and CPT codes, detailed clinical notes, relevant test results, and a clear justification for the medical necessity of the service. Submitting thorough and accurate information upfront is paramount to avoiding delays and denials.

- Step 4: Submit Request

- The prior authorization request is then submitted to the insurance company through their preferred channels. These can include online portals (electronic prior authorization or ePA), fax, or phone calls. Electronic submissions are generally recognized as faster, more efficient, and effective in reducing administrative errors.

- Step 5: Track Status & Follow Up

- Following submission, the provider’s office actively monitors the request’s status. This often involves utilizing online portals or dedicated phone lines and responding promptly to any requests for additional information or clarifications from the insurer. This phase can frequently involve time-consuming back-and-forth communication between the provider and the payer.

- Step 6: Receive Decision

- An insurance company clinician, typically a physician or nurse, reviews the request against their established medical necessity criteria and makes a determination. The outcome can be an approval, a denial, a request for more information, or a recommendation for an alternative, often less costly, treatment.

The process of prior authorization can occur in two primary ways: retrospectively or prospectively. In a retrospective process, a provider prescribes medication, and the patient attempts to pick it up, only for the pharmacy to receive a rejection from the patient’s plan. The pharmacy then initiates the prior authorization request, sending it to the provider to complete and submit. This adds an extra, unnecessary step and, on average, delays patient access to medication by 13.2 days.

This means that patients are often delayed in starting therapy due to administrative failures that occur after they have already sought care and are expecting treatment. The contrast with a prospective process, where the provider initiates the prior authorization at the point of prescribing, allows for faster medication access and improved patient outcomes. This situation underscores the urgent need for wider adoption of prospective, in-workflow electronic prior authorization (ePA) solutions.

How Long Does Prior Authorization Take?

The timeline for prior authorization approval can vary significantly based on the complexity of the request, specific payer policies, and the urgency of the treatment.

- Standard Requests: These typically receive a response within 24 to 72 hours.

- Urgent/Expedited Requests: For cases demonstrating critical medical necessity, requests can be processed within 24 to 72 hours. Some state laws, such as in Indiana and New Jersey, mandate responses within 24 hours for urgent medication requests and 72 hours for urgent diagnostics/procedures.

- Complex Cases / High-Cost & Specialty Drugs: These may take longer, ranging from 7 to 10 days, or even 10 to 30 days, especially if the insurer requires more extensive medical documentation or further review.

- Appeals: If a request is denied and an appeal is filed, the process can extend the timeline by several weeks to months, depending on the number of review levels involved.

Factors Affecting Processing Speed

Several key factors can significantly influence the processing speed of a prior authorization request:

- Submission Method: The transition from traditional fax and paper-based submissions to electronic prior authorization (ePA) is a major determinant of speed. ePA is significantly faster and more accurate, capable of reducing processing times from days to hours.

- Documentation Quality: Incomplete, incorrect, or insufficient documentation, such as missing medical history or a lack of clear clinical justification, is a primary cause of delays and denials. This often leads to extensive back-and-forth communication between providers and insurers.

- Payer Variability and Lack of Standardization: Each insurance company frequently maintains its own unique policies, criteria, forms, and submission methods. This absence of standardization across different insurers makes the process confusing and cumbersome for healthcare providers, resulting in inconsistent processing times.

- Communication Gaps: Miscommunication or a lack of real-time integration among physicians, pharmacies, and insurers can cause significant delays, as requests may become stalled due to missed updates or misunderstandings.

- Administrative Burden on Providers: Physicians and their staff dedicate a substantial amount of time—an average of 13 to 16 hours per week—to managing prior authorization requests. This administrative workload diverts valuable resources and time away from direct patient care, contributing significantly to delays.

While a primary stated purpose of prior authorization is to control overall healthcare costs, numerous reports reveal that it imposes substantial administrative costs on healthcare providers. The time physicians and their staff spend on prior authorization requests, coupled with the necessity for many practices to assign dedicated staff solely to these tasks, represents an “unreimbursed cost of providing care.” This creates a hidden cost within the system, potentially leading to higher overall system expenditures or a reduction in the time and resources available for direct patient care.

Table 2: Prior Authorization Timelines:

| Request Type | Typical Response Time | Key Factors Influencing Time |

| Standard Requests | 24 to 72 hours | Electronic vs. Paper Submission, Completeness of Documentation, Payer Variability |

| Urgent/Expedited Requests | 24 to 72 hours (often faster for critical medical necessity) | Demonstration of critical medical necessity, State laws mandating faster responses |

| Complex Cases / High-Cost & Specialty Drugs | 7 to 10 days, or even 10 to 30 days | Extensive medical documentation required, Further insurer review, Manual processing |

| Appeals | Several weeks to months | Number of review levels, Required documentation for appeal, Insurer response times |

When Prior Authorization is Denied: Your Rights and Next Steps

Understanding Why Your Request Was Denied

A denial of prior authorization means your health plan has determined the requested treatment, service, or medication does not meet their specific criteria, often based on the information submitted. Understanding the precise reason for a denial is the crucial first step in addressing it. Common reasons for denials include:

- Incomplete or inaccurate information/paperwork: This is a very frequent cause, stemming from issues such as a wrong billing code, a misspelled patient name, or a lack of sufficient clinical justification.

- Lack of medical necessity: The insurer determines, according to their guidelines, that the service or medication is not medically necessary for the patient’s condition.

- Failure to meet specific criteria: The request may not align with specific, often complex, criteria set by the insurer for coverage of a particular service or drug.

- Recommendation for an alternative: The health plan may suggest a less costly, yet equally effective, alternative treatment or medication, requiring the patient to try this option first.

- Procedural error: The service was received before obtaining the necessary prior authorization approval, leading to a retrospective denial of payment.

- Out-of-network provider: The healthcare provider is not part of the patient’s insurance plan’s network.

Your Rights and the Appeal Process

It is paramount to understand that a prior authorization denial is not a final decision; many denials can be successfully appealed. Under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), most private health insurance plans are mandated to offer a two-level appeals process: an internal appeal directly with the insurer, followed by an external review if the internal appeal is upheld. Medicare beneficiaries also possess robust appeal rights with specific steps and timelines tailored to their plans.

Here are the key steps in navigating the appeal process:

- Request a Denial Letter: Obtain this formal document from the insurance company. It will provide the denial code, the specific reasoning, and detailed instructions on how to appeal.

- Understand the Denial Reason: Work closely with your healthcare provider’s office to interpret why the request was denied. Often, denials stem from administrative or clerical errors rather than a lack of clinical justification.

- Gather Supporting Documentation: A strong appeal is built upon comprehensive clinical documentation. This includes detailed medical records, relevant test results, a compelling letter of medical necessity from your doctor (signed), and any records of prior failed treatments. Including references to supporting clinical guidelines or peer-reviewed articles can further strengthen the case.

- Internal Appeal: Submit a detailed appeal letter directly to your insurance company. This letter should clearly explain the medical necessity of the treatment, service, or medication. Patients typically have 60 to 180 days from the denial date to file this appeal. Standard internal appeals are usually reviewed and decided within 15 to 60 days.

- Peer-to-Peer Review: Your healthcare provider can request a direct discussion with the insurance company’s medical reviewer. During this “peer-to-peer” review, your provider can explain why the treatment is medically necessary, often providing additional context. These reviews are typically scheduled within 5 to 10 business days.

- External Review: If your internal appeal is unsuccessful, you have the right to request an independent third-party review. This external review is conducted by an organization not connected to your insurance company, often managed through your state insurance department or health exchange. Decisions from external reviews are generally issued within 45 days after the request is accepted.

- Expedited Appeals: For urgent medical situations where waiting for a standard decision could seriously harm your health, you have the right to request an expedited (fast) appeal. These urgent appeals should be resolved within 72 hours or sooner.

The frequent overturning of initial prior authorization denials on appeal, with some studies showing reversal rates as high as 39%, suggests that the prior authorization process, as currently implemented, may sometimes function to deter or delay care rather than solely to ensure true medical necessity. This pattern indicates that initial denials are not always based on a thorough, clinically informed review, but rather on a default “no” or an absence of complete information. This effectively shifts the burden of proof and additional administrative work onto the patient and their provider.

When You Might Pay Out-of-Pocket

If prior authorization is not obtained before a service or medication is received, the health plan may not cover the cost, leaving the patient responsible for the full bill. This situation is particularly relevant if a patient chooses to use an out-of-network healthcare provider and does not personally obtain the necessary prior authorization.

While many insurer contracts restrict providers from directly billing patients for services denied solely due to a lack of prior authorization, the absence of insurance coverage means the patient could still face significant and unexpected financial obligations. In some unfortunate cases, patients who are denied coverage may be compelled to accept less effective or less tolerable “second-choice” treatment options, or they may experience “financial toxicity” due to substantial out-of-pocket expenditures for their preferred or medically necessary care.

Table 3: Essential Documents for a Prior Authorization Appeal

| Document Type | Description & Importance |

| Original Denial Letter | This formal document from your insurer outlines the denial code, specific reasons for denial, and instructions for appeal. It is the starting point for your appeal. |

| Comprehensive Medical Records/Clinical Notes | Detailed patient history, physician’s notes, and clinical observations justifying the medical necessity of the requested service or medication. This is crucial evidence. |

| Letter of Medical Necessity from Your Doctor (signed) | A compelling letter from your prescribing physician or specialist explaining why the specific treatment is the most appropriate and medically necessary for your condition. A signed letter adds significant weight. |

| Relevant Test Results/Diagnostic Imaging | Copies of any lab results, X-rays, MRIs, CT scans, or other diagnostic reports that support your diagnosis and the need for the requested treatment. |

| Detailed Treatment History (especially records of failed alternative treatments) | Documentation of previous treatments, medications, or therapies tried, and why they were ineffective or caused intolerable side effects. This demonstrates adherence to “step therapy” requirements. |

| CPT and ICD-10 Codes (used in original request) | The specific codes that identify the diagnosis (ICD-10) and the procedure/service (CPT) originally submitted. Ensures consistency and accuracy in the appeal. |

| All Correspondence with Your Insurer Regarding the Denial | Keep a record of all communications, including emails, faxes, and detailed notes from phone calls (with dates, times, and names of representatives). |

| Letters from Specialists or Second Opinions (if applicable) | Additional letters from other specialists or a second opinion that corroborate the medical necessity of the requested care. |

| References to Peer-reviewed Articles or Clinical Guidelines (if supporting your case) | If there are established clinical guidelines or scientific literature that support the use of the requested treatment for your condition, include these references. |

| Patient Consent Form (if a provider or advocate submits on your behalf) | If someone other than the patient is submitting the appeal, a signed consent form authorizing them to act on the patient’s behalf is often required. |

Tips for Patients: Navigating Prior Authorization Smoothly

Be Proactive and Informed

Taking an active role in understanding prior authorization can significantly ease the process. Patients should take the time to learn what prior authorization entails and why it is required, as many are unaware of its complexities and potential impact on their care.

When a doctor prescribes a new medication or suggests a procedure, it is advisable to ask early if prior authorization will be required for your specific health plan, as requirements vary considerably. Patients should also review their health insurance plan documents, often accessible online, for lists of services and medications that typically require prior authorization. Furthermore, a common reason for denials is using an out-of-network provider; therefore, always confirming that your healthcare provider is in-network is a crucial preventive step.

Communicate Effectively

Clear and consistent communication with all parties involved is vital. Patients should maintain open dialogue with their doctor’s office, as the provider’s team is primarily responsible for initiating and managing the prior authorization process. Ensuring they have all updated insurance and medical information, and clearly communicating the urgency of the case if applicable, can be beneficial.

Patients should not hesitate to follow up with their doctor’s office about the status of their prior authorization request. While the office tracks these requests, a proactive inquiry can sometimes help expedite the process or identify issues early. If a request is denied, promptly obtaining a copy of the official denial letter and working collaboratively with the provider to understand the exact reason for the denial is essential.

Maintain Records and Documentation

Diligent record-keeping can prove invaluable. Patients should create a personal file for their healthcare documents, saving copies of all relevant paperwork, including prior authorization requests, denial letters, test results, and any correspondence (emails, notes from phone calls with dates and names) with their insurer or provider.

Even minor administrative errors, such as a misspelled name or an incorrect insurance ID, can lead to denials. Therefore, always confirming the accuracy of personal details and the information submitted on one’s behalf is a critical step.

Leveraging Support and Appeals

Patients should be aware of available support systems and their rights. Considering patient advocacy organizations, such as the Patient Advocate Foundation or Solace , can provide invaluable assistance in understanding denials, coordinating documentation with doctors, drafting and submitting appeal letters, and even escalating cases with insurers.

It is crucial to remember that many prior authorization denials are overturned upon appeal. Understanding one’s rights to both internal and external reviews is key to a successful appeal. If waiting for a standard decision could seriously harm health or delay critical treatment, patients have the right to request an expedited appeal. While healthcare providers are primarily responsible for initiating prior authorization requests, the emphasis on patients being “proactive” and “informed” suggests a significant portion of the administrative follow-up burden is effectively shifted onto them. This can exacerbate health disparities, as individuals who lack the time, resources, or health literacy may struggle to effectively advocate for themselves.

The Future of Prior Authorization: What Changes Are Coming?

Push for Electronic Prior Authorization (ePA)

There is a strong and growing industry-wide push for standardized electronic prior authorization (ePA) processes. ePA solutions, particularly when integrated with Electronic Health Records (EHRs), have demonstrated significant potential to improve accuracy, reduce staffing requirements, accelerate turnaround times from days to hours, and minimize administrative errors. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has been actively working on regulations to streamline prior authorization processes for Medicaid and Medicare Advantage plans through new electronic standards, with enforcement beginning in 2022.

Legislative and Regulatory Reforms

Significant legislative and regulatory reforms are underway at both state and federal levels to address the challenges posed by prior authorization.

- State-Level Action: State governments are actively passing legislation to mitigate the burdensome insurance practice that delays care and increases clinician burnout.

- Indiana enacted a prior authorization reform bill requiring insurers to respond to urgent requests within 24 hours and non-urgent requests within 48 hours. This law also mandates peer-to-peer review in appeals of denials, upholds prior authorizations from a patient’s previous insurer for at least 90 days, and requires public sharing of services needing prior authorization.

- Iowa and Nebraska have enacted similar legislation setting stricter timelines, transparency measures, and reporting requirements, with Nebraska specifically limiting AI-based denials.

- Montana has passed bills requiring adverse determination appeals to be reviewed by a physician in the same specialty, extending prior authorizations for chronic conditions to the length of treatment, prohibiting retroactive denials, and requiring electronic prior authorization requests.

- New Jersey’s recent law shortens response times to 24 hours for urgent medication requests and 9 days for nonurgent electronic diagnostic/procedure requests, with missed deadlines resulting in automatic authorizations.

- Federal Initiatives: Federal efforts include CMS regulations aimed at streamlining prior authorization for Medicaid and Medicare Advantage plans. Proposed legislation, such as H.R. 3173, would require CMS to implement an electronic prior authorization program for Medicare Advantage plans with real-time decision-making capacity.

- Industry Pledges: Major health insurance carriers have voluntarily pledged to make changes to streamline prior authorization, including reducing the volume of in-network medical prior authorizations, honoring previous carriers’ prior authorizations for new enrollees (provided the service is covered), improving communication on denials with clear and personalized language, and expanding real-time responses for approvals. They also commit that all prior authorization denials based on medical necessity will be reviewed by a licensed and qualified clinician. However, these pledges currently do not address prior authorization in prescription-drug benefits and are limited to certain health-plan products.

Role of Technology and Automation (Beyond ePA)

Beyond electronic prior authorization, the broader adoption of technology and automation holds promise for improving the process. Automating appropriate administrative components through AI tools can help address concerns voiced by many physicians and prescribers. However, the complete transition to AI-supported prior authorization models comes with its own set of challenges and ethical considerations, including potential moral dilemmas.

Drug Manufacturers and Patient Access Support

Prior authorization creates barriers to market access for pharmaceutical companies. When a company’s product requires prior authorization, healthcare providers are more likely to switch to a product that does not require one, even if the company’s product is more effective and safe for the patient. If healthcare providers consistently encounter prior authorization requirements for a particular product, they may refrain from prescribing it altogether.

For pharmaceutical companies, market access is crucial. They are increasingly involved in helping doctors navigate the prior authorization process, often by having staff certified as prior authorization specialists. This support can improve the approvability of prior authorization requests and product pull-through, increasing the chances that a product reaches patients who need it. Manufacturer-sponsored patient assistance programs (PAPs) also play a significant role. These programs provide free or low-cost medications to qualifying patients, particularly those with limited or no health insurance coverage.

Through their prior authorization programs, manufacturers advocate to payers for coverage, providing truthful and accurate healthcare economic information about their products to facilitate coverage and reimbursement decisions. This advocacy ensures that necessary and pertinent clinical information, such as diagnosis, lab results, and treatment history, which is not always available through online claims adjudication, is provided to justify coverage decisions. The challenges presented by prior authorization are not isolated to a single group; they create a complex web of negative consequences that impact patients, healthcare providers, and pharmaceutical companies across the healthcare ecosystem.

FAQs About Prior Authorization

How do I know if my medication needs PA?

Not every prescription requires prior authorization. Your doctor or pharmacist may inform you if a PA is needed for your specific medication. You can also check your health plan’s online account or plan documents, or call your insurance company directly for a list of medications that typically require PA. Common categories include brand-name drugs when cheaper generic options are available, high-cost specialty drugs, or those with a high potential for misuse.

Can I start treatment while waiting for PA approval?

Generally, no. Without prior authorization, your health plan may not cover the cost of your treatment or medication. In some cases, if a PA is already in process, an insurer

might allow you to have a short-term supply of the medication until the prior authorization is approved, but you may need to specifically request this exception. It is crucial to wait for approval to avoid unexpected out-of-pocket costs.

What happens if I use an out-of-network provider?

If you choose to use an out-of-network healthcare provider, you are typically responsible for obtaining the prior authorization yourself. If you do not secure it, the treatment or medication might not be covered by your health plan, or you may face significantly higher out-of-pocket costs. While many insurer contracts may restrict providers from directly billing patients for services denied solely due to a lack of prior authorization, you could still be responsible for the full amount if coverage is denied.

How often do I need to renew PA for ongoing treatments?

Yes, you may need to renew prior authorization for ongoing treatments. Your health plan may require your provider to confirm that ongoing services or medications continue to be beneficial and medically necessary. Some state laws, like those in Montana, are extending prior authorizations for chronic conditions to cover the entire length of treatment, and some states mandate upholding prior authorizations from a patient’s previous insurer for at least 90 days. However, this varies by state and individual health plan, so always check your specific policy.

Conclusion

Prior authorization, a pervasive mechanism in the US healthcare system, is fundamentally designed to control costs and ensure that medical services and medications are medically necessary and appropriate. However, the current implementation of this process often presents a paradox: while intended to promote efficiency and patient safety, it frequently results in significant delays in care, substantial administrative burdens for healthcare providers, and, in many cases, patients abandoning necessary treatments. This inherent tension between the stated goals and real-world outcomes underscores a critical imbalance within the healthcare system.

The expansion of prior authorization requirements, even to generic medications and ongoing treatments, indicates an evolving and broadening interpretation of “medical necessity” by insurers. This expansion can inadvertently create additional administrative hurdles for patients and providers, leading to unexpected delays and potentially eroding trust. The frequent discovery of prior authorization requirements only at the point of care, such as the pharmacy counter, further highlights a systemic lack of transparency that leaves patients feeling unprepared and frustrated.

The administrative burden on healthcare providers, who spend considerable time managing prior authorization requests, represents a hidden cost within the system. This diverts resources from direct patient care and contributes to provider burnout, suggesting that the “cost control” achieved by insurers may come at the expense of overall system efficiency and quality of care. Furthermore, the high rate of initial denials, many of which are later overturned on appeal, points to a “deny first” approach that unnecessarily prolongs the process and adds to the administrative load for all stakeholders.

Despite these challenges, there is a clear movement towards reform. The widespread adoption of electronic prior authorization (ePA) holds significant promise for streamlining processes, improving accuracy, and reducing turnaround times. Legislative and regulatory efforts at both state and federal levels are actively working to mandate stricter response times, increase transparency, and ensure fairer review processes. Additionally, pharmaceutical manufacturers are increasingly providing support to help patients and providers navigate prior authorization, recognizing its impact on patient access to crucial medications.

Ultimately, navigating prior authorization smoothly requires a proactive and informed approach from patients, effective communication with healthcare providers, diligent record-keeping, and a willingness to leverage available support systems and appeal rights. While the process remains complex, ongoing reforms and technological advancements offer hope for a more efficient and patient-centered future in healthcare approvals.

Interactive Prior Authorization Tools for Patients