The FDA establishes rigorous microbiological and chemical standards for high-purity water systems used in pharmaceutical manufacturing. These standards are fundamental to ensuring the safety, efficacy, and sterility of drug products, regardless of whether they are produced domestically or internationally. Water is not merely an ingredient in pharmaceutical manufacturing—it is a critical process material whose quality directly impacts product safety and regulatory compliance. This comprehensive guide covers FDA and USP specifications for Water for Injection (WFI) and Purified Water, system design principles, complete validation lifecycle, biofilm prevention strategies, and regulatory compliance requirements—essential knowledge for quality assurance professionals, manufacturing engineers, regulatory specialists, and pharmaceutical plant managers.

In this guide, you will learn:

- Microbiological limits and testing standards for WFI and purified water

- FDA specifications versus USP monograph requirements

- Complete system design and component selection guidelines

- Validation phases: Design Qualification (DQ) through Performance Qualification (PQ)

- Biofilm formation, prevention, and control strategies

- Regulatory compliance requirements and documentation standards

Understanding Water Categories and FDA Specifications

Water Classifications in Pharmaceutical Manufacturing

The FDA recognizes multiple water categories, each with distinct specifications and applications based on their intended use. Understanding these classifications is critical for proper water system selection and validation strategy.

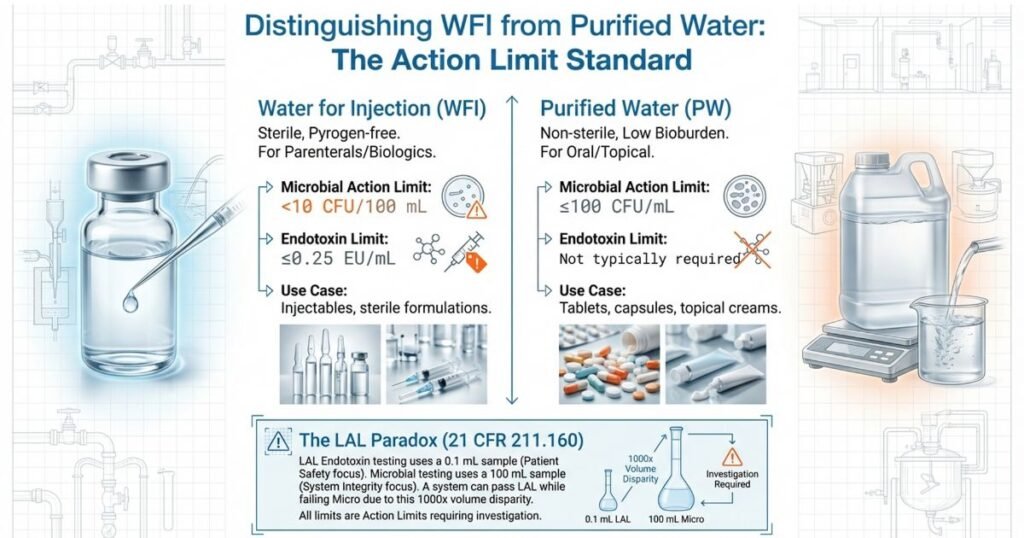

Water for Injection (WFI): The highest-purity water classification, WFI is required for parenteral products (injections), biologics, sterile drug manufacturing, and any formulation that will be sterilized in its final container. WFI is produced through distillation or reverse osmosis with electrodeionization (RO-EDI) and maintained at elevated temperatures to prevent microbial growth and pyrogen accumulation. WFI must meet the most stringent microbiological and chemical specifications due to direct patient contact and inability to filter during administration.

Purified Water (PW): Used for non-sterile pharmaceutical preparations, including oral solutions, topical products, oral solid manufacturing processes, and non-critical manufacturing steps. Purified water meets rigorous standards but less stringent than WFI. While still produced under controlled conditions, purified water allows higher microbial levels and does not require pyrogen removal as rigorously as WFI.

Potable Water: May be used for certain non-critical manufacturing steps under specific FDA approval; rarely used for pharmaceutical product manufacture.

Each water category has distinct microbiological and chemical requirements established by USP monographs and FDA 21 CFR 211 regulations.

FDA Microbiological Limits for Water for Injection (WFI)

WFI specifications demand the highest microbiological quality among pharmaceutical waters. The FDA and USP establish action limits—not pass/fail thresholds—meaning when any limit is approached or exceeded, the facility must investigate root causes and implement corrective actions. According to FDA policy, no limit for pharmaceutical water is a simple pass/fail; all limits are action limits that trigger mandatory investigation and product impact assessment.

| Parameter | Limit | Regulatory Reference | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microbial Count | <10 CFU/100 mL | FDA/USP <1231> | Absence of viable microorganisms |

| Endotoxins (Pyrogens) | ≤0.25 EU/mL | USP <85> LAL Test | Limulus Amebocyte Lysate method |

| Absence of Pathogens | Required | FDA 21 CFR 211.160 | Pseudomonas, Coliform, E. coli absent |

| Conductivity | ≤1.3 µS/cm @ 25°C | USP <645> | Stage 1, 2, 3 testing required |

| Total Organic Carbon (TOC) | ≤500 ppb | USP <643> | Indicates organic contamination risk |

Critical Distinction: The microbiological limit of <10 CFU/100 mL represents sterility of the WFI system. This limit is not arbitrary; it reflects the risk threshold for parenteral product contamination. When WFI production exceeds this limit, the entire batch is considered potentially compromised and must be diverted from production use.

FDA Microbiological Limits for Purified Water

Purified water specifications are less stringent than WFI but maintain rigorous standards to protect non-sterile product quality and prevent patient exposure to significant microbial loads. While purified water does not require pyrogen removal as stringently as WFI, it must still meet robust microbiological standards. The FDA follows USP guidelines for purified water, recognizing that even non-sterile products require microbiological control to ensure product stability, safety, and efficacy.

| Parameter | Limit | Standard | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microbial Count | ≤100 CFU/mL | USP XXII/USP <1231> | Action limit for batch disposition |

| Absence of E. coli, Pseudomonas, Coliform | Required | FDA 21 CFR 211.160 | Must be absent; any detection triggers investigation |

| Conductivity | ≤1.3 µS/cm @ 25°C | USP <645> | Ionic purity indicator |

| TOC | ≤500 ppb | USP <643> | Organic contamination indicator |

Application Note: Oral solid products (tablets, capsules) may be manufactured with purified water under standard conditions. However, antacids and certain oral products require enhanced microbial control due to their therapeutic classification and patient population vulnerability. This enhanced control is typically achieved through reduced alert limits (40-50 CFU/mL instead of standard 100 CFU/mL) and increased sampling frequency.

The Critical Endotoxin vs. Microbial Testing Relationship

A fundamental distinction exists between endotoxin and microbial testing for WFI that significantly impacts quality assurance strategy. WFI can pass the LAL (Limulus Amebocyte Lysate) endotoxin test but fail microbial limits. This occurs because the LAL endotoxin test uses only 0.1 mL of sample volume, whereas microbial testing uses 100 mL—making microbial testing a far superior indicator of system contamination and biofilm presence.

The endotoxin limit of ≤0.25 EU/mL is specifically designed to prevent pyrogenic (fever-causing) reactions in patients receiving injectable products. Endotoxins are heat-stable bacterial cell wall components that remain intact even after microbial cells are killed by autoclaving or heat treatment. This is why WFI production must focus on endotoxin removal (via distillation or RO-EDI with appropriate feed water pretreatment) rather than simply sterilizing existing water.

Best Practice Recommendation: Testing both endotoxin and microbial limits is mandatory for comprehensive WFI quality assurance. Do not rely on endotoxin testing alone to confirm WFI system integrity. Biofilm formation, feedwater spikes, and heat exchanger contamination can allow microbial growth without proportional endotoxin increases, making microbial testing the superior indicator of system cleanliness.

System Design According to FDA Standards

Design Qualification: The Foundation of Compliance

Effective water system design begins with Design Qualification (DQ), a critical but often overlooked validation phase that establishes system scope, intended use, required specifications, and risk controls before equipment procurement. FDA inspectors frequently cite inadequate DQ as a major deficiency because poor design decisions made at DQ stage cannot be adequately corrected during installation or operation.

Design Qualification Activities:

- Develop User Requirements Specification (URS) defining water quality requirements, flow rates, temperature setpoints, sampling accessibility, sanitization strategy, and hold time requirements

- Conduct Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) identifying contamination risks, including biofilm formation, dead-leg stagnation, heat exchanger leakage, and feedwater contamination

- Link all requirements to testable verification criteria and establish traceability matrix

- Document regulatory references: FDA 21 CFR 211, USP <645>, <643>, <1231>, and latest FDA inspection guidance

- Assess risk to products: Determine which drug products will use this water system and their sterility/pyrogen requirements

- Define sanitization strategy: Will system use continuous hot circulation, periodic chemical sanitization, or hybrid approach?

Design considerations depend on product category:

- Parenterals & Biologics: Require WFI; must include pyrogen-free production strategy and validated thermal or chemical sanitization

- Ophthalmics & Inhalation Products: Require sterile water for injection; must incorporate aseptic processing or sterile fill validation

- Oral Solids: May use purified water; require robust microbial monitoring at multiple system points

- Antacids & Special Oral Products: Require enhanced microbial controls even in PW systems due to therapeutic vulnerability

Risk assessment at design stage should address: potential contamination pathways (feedwater quality, dead legs, biofilm formation sites), system uptime requirements, sampling accessibility, sanitization effectiveness, temperature maintenance capability during power outages, and contingency procedures.

Temperature Management and System Classification

Temperature is a critical design parameter that determines system sanitization effectiveness, biofilm formation risk, and microbial control strategy. FDA guidance and practical experience have established temperature ranges and continuous monitoring requirements as non-negotiable elements of water system control.

Optimal Temperature Strategy:

- Target Temperature: 80°C for hot circulating WFI systems (provides maximum self-sanitization effect)

- Acceptable Operating Range: 75-80°C for continuous operation (minimizes microbial recovery)

- Minimum for Hot Systems: 65°C (though ≥70°C strongly preferred; below 65°C loses biofilm prevention benefit)

- Critical Alert: Even brief temperature fluctuations from 80°C to 70°C increase microbial recovery and trigger biofilm development—continuous temperature monitoring with alarms is essential

Brief temperature dips represent one of the most common reasons for unexplained microbial excursions in pharmaceutical water systems. A heating system failure lasting only 2-3 hours can allow biofilm shedding throughout the system over the following 24-48 hours.

System Types and Selection:

| System Type | Description | Microbial Control | Preferred Application | Maintenance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Circulating (Hot) | Continuously circulated at 65-80°C | Lower risk; self-sanitizing at ≥75°C | WFI systems; high-volume users | Thermal sanitization; dead-leg elimination |

| Non-Recirculating | Water produced on-demand; not continuously circulated | Higher risk; depends on sanitization | Low-volume users; backup systems | Requires validated chemical sanitization |

| Hybrid | Combination: some points circulated, others on-demand | Moderate; variable by zone | Mixed-use facilities | Zone-specific sanitization strategies |

For WFI held at ambient temperature (non-recirculating systems), FDA guidance requires batch disposition (disposal or diversion to non-WFI use) within 24 hours of production. Holding longer than 24 hours without heat creates biofilm risk and endotoxin formation from dead microorganism accumulation.

High-Purity Water System Components and Contamination Risk Control

Water system design requires careful component selection and integration to prevent each identified contamination pathway. Understanding component-specific risks allows proactive design controls.

Feed Water Pretreatment

Feed water quality directly impacts WFI production success. Poor feed water quality forces the distillation still or RO system to work harder, reducing endotoxin removal efficiency and increasing breakthrough risk. Pre-demineralization and appropriate pretreatment prevent: microbiological contamination from surface water, endotoxin spikes (documented risk when feedwater validation fails), equipment scaling and corrosion, and membrane fouling (for RO systems).

Best practice includes: carbon filtration (removes chlorine, organics), microfiltration (removes suspended particles), softening (removes hardness ions that cause scaling), and periodic feedwater monitoring for microbial and endotoxin content. Some facilities conduct quarterly feedwater validation to detect seasonal variations in source water quality.

Distillation vs. RO-EDI Technology for WFI Production

Historically, distillation was the only FDA-accepted method for WFI production. Today, Reverse Osmosis with Electrodeionization (RO-EDI) is widely accepted by FDA and EMA, particularly in biotech applications, provided rigorous validation proves equivalence to distillation.

RO-EDI Advantages:

- More energy-efficient than distillation (lower operational cost)

- Faster production (real-time availability vs. batch distillation)

- Scalable for high-volume applications

- Increasingly preferred in biotech industry

Critical RO-EDI Validation Requirements:

- Distillation manufacturers guarantee ≥2.5 to 3-log endotoxin reduction (typically 250 EU/mL in feedwater → <0.25 EU/mL WFI)

- Feed water quality must be maintained; spikes to 250 EU/mL are unacceptable input

- Series configuration (two RO membranes in sequence) mandatory for WFI

- Ultraviolet light pretreatment recommended to reduce microbial load

- Post-RO sanitization strategy must equal distillation (continuous hot circulation or periodic chemical treatment)

Most pharmaceutical facilities now accept either distillation or RO-EDI for WFI production, provided validation documentation demonstrates equivalent endotoxin removal and microbial control.

Heat Exchangers: Critical Still Components

Heat exchangers are principle components of distillation stills that concentrate heat for water evaporation. Key design and operational controls prevent contamination:

- Double Tube-Sheet Heat Exchangers minimize contamination risk from leakage; if outer chamber leaks, contaminated fluid cannot enter distillate chamber

- Pressure Monitoring at each heat exchanger point ensures clean fluid pressure exceeds contaminated fluid pressure, preventing backflow

- Gauge Installation detects WFI leakage at valve points early, before system contamination

- Conductivity Meters Cannot Assess Microbial Quality—ionic purity of distilled and deionized water appears identical despite microbial differences; this limitation necessitates microbial testing independent of conductivity monitoring

Common heat exchanger problems causing WFI contamination include: leaking gaskets allowing feedwater intrusion, failed pressure relief valves, and temperature control failures causing steam condensation in distillate lines.

Holding Tanks: Temperature and Vent Filter Management

Holding tanks maintain WFI temperature and serve as buffer storage for production demand. Jacketed tanks maintain setpoint temperature through heat application. The vent filter is a critical component that prevents atmospheric contamination:

- Vent Filter Integrity Testing must be performed regularly (typically monthly or quarterly depending on contamination history) to ensure filter remains functional

- Hydrophobic Vent Filters prevent water from blocking filter pores under typical operating conditions; hydrophobic filters repel water while allowing air exchange

- Condensate Water Prevention requires filters designed to handle humid conditions and periodic displacement of trapped moisture

- Temperature Monitoring on Holding Tank is essential; even brief thermal dips compromise self-sanitization

Vent filter failure is a documented cause of holding tank contamination. Filters can become hydrophilically blocked (water-logged) when condensation repeatedly washes over them, preventing air breathing and allowing vacuum conditions that draw external microorganisms inward.

Pumps: Minimizing Static Contamination Sites

Static pump reservoirs create low-flow dead zones where biofilms readily establish and rapidly develop. Design and operational considerations for pump safety:

- Minimize Static Operation: Use continuous or frequent circulation; avoid periodic pump activation (intermittent use increases biofilm risk 10-fold)

- Pump Reservoir Design: Preferably heated and insulated to maintain system temperature; unheated reservoirs become cold spots for microbial growth

- Drainage Strategy: Pump wetted surfaces should drain completely when circulation stops; residual water in impeller housing creates biofilm nursery

- Regular Sanitization: Pump wetted surfaces require periodic chemical or thermal sanitization separate from main system sanitization

Pumps have been identified in FDA inspections as frequent biofilm sources, particularly when pumps operate intermittently or during facility downtime.

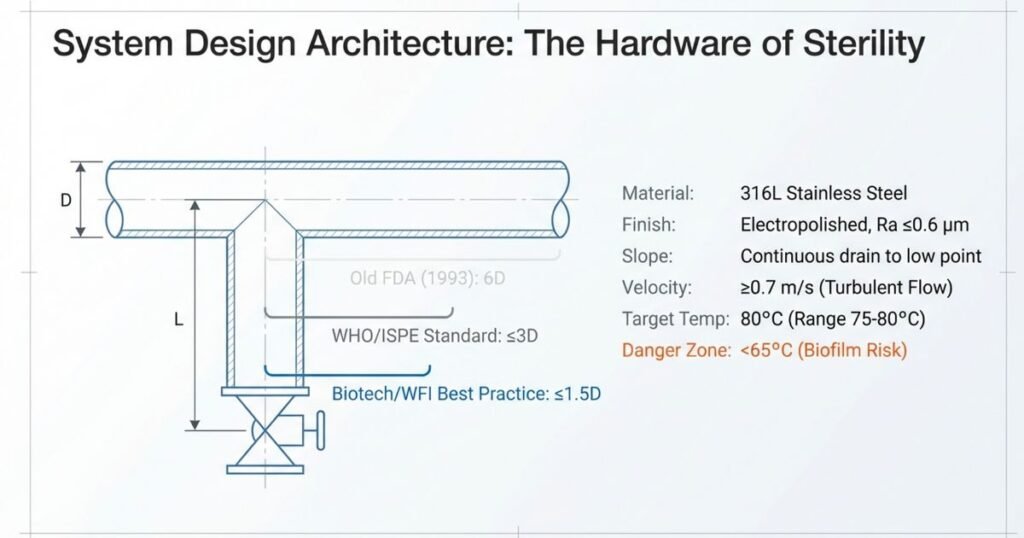

Piping Materials and Dead-Leg Standards: Critical Design Element

Piping material selection and dead-leg elimination represent two of the most critical design decisions affecting long-term system reliability.

Piping Material Selection:

- 316L Stainless Steel: Industry standard, highly polished (Ra ≤0.6 µm surface roughness), resistant to corrosion and extractable contamination at elevated temperatures. Electropolishing improves surface finish, reduces corrosion pits, and inhibits biofilm attachment.

- PVDF Piping: Can tolerate high temperatures (up to 95°C) without leaching extractables; however, overheating causes plastic sagging and loss of fusion-point integrity. Requires careful thermal management to avoid leakage at joints. Less commonly used than stainless steel due to application complexity.

Dead-Leg Standards (Critical Design Element):

Dead legs are stagnant branch pipes where water cannot circulate effectively, creating biofilm reservoirs. Current industry standards for acceptable dead-leg size vary based on system type and risk profile:

| Standard | L/D Ratio | Application | Industry Reference | Current Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDA 1993 Guidance | ≤6D | Hot systems (>75°C) | FDA Inspection Guide | Outdated; still referenced by some inspectors |

| WHO TRS 970 | ≤3D | Standard pharma water systems | WHO Technical Report Series | Current best practice for most applications |

| ISPE Baseline Guide | ≤3D | Recommended standard | ISPE Water Systems | Current best practice, widely adopted |

| ASME BPE-2019 | ≤2D | High-risk applications | American Society of Mechanical Engineers | Modern standard, increasingly adopted |

| Biotech Industry | ≤1.5D | Sterile manufacturing, high-risk products | FDA Biotech Guidance | State-of-the-art; recommended for critical applications |

Definition: L = length measured from internal pipe wall of main circulation line to the center line of the point-of-use valve; D = internal diameter of branch pipe.

Modern Industry Practice: Dead-leg-free design is strongly preferred where feasible. When unavoidable, design to ≤1.5D for critical WFI applications serving parenteral products. Facilities manufacturing oral solid products may tolerate up to 3D dead-legs for purified water systems, provided enhanced microbial monitoring compensates for increased stagnation risk.

Piping Design Principles:

- Continuous slope (no low points that trap water or allow sediment accumulation)

- Dead-leg-free or minimized to ≤1.5D for critical applications

- Smooth, polished interior surfaces (Ra ≤0.6 µm measured on final installed piping) to prevent biofilm attachment and reduce surface area available for microbial colonization

- Hygienic fittings (flush-mounted, low-profile valve connections) to minimize dead space and facilitate cleaning

Each dead leg should be mapped during Installation Qualification (IQ), with L/D ratios calculated and documented in validation files. Dead-leg monitoring (elevated alert limits, increased sampling frequency) should be implemented for any dead legs that cannot be eliminated.

Reverse Osmosis Systems: Modern WFI Production Alternative

RO technology is increasingly used in pharmaceutical water production, particularly in biotech applications where energy costs and environmental concerns make distillation less attractive. When properly designed and validated, RO-EDI systems can produce WFI equivalent to distillation.

RO System Design for Contamination Control:

- Series Configuration: Two RO membranes in series increase rejection and microbial control; single-stage RO is not acceptable for WFI

- UV Pre-treatment: Ultraviolet light installed before RO reduces microbial bioburden entering membranes; prevents membrane biofouling

- Heat Integration: Install heat exchangers upstream of RO to raise water temperature to 75-80°C—this reduces microbial survival in RO unit, enhances system reliability, and maintains elevated temperature in distribution system

- Post-RO Sanitization: Maintain hot recirculation post-RO (80°C continuous circulation) to prevent biofilm formation in distribution piping; without adequate post-RO temperature control, RO systems can become biofilm sources

- Membrane Integrity Monitoring: Regular pressure drop testing and conductivity trending detects membrane breach before contamination occurs

Modern facilities often combine RO-EDI with continuous hot circulation and periodic chemical sanitization to achieve robustness equivalent or superior to traditional distillation.

Water System Validation Lifecycle

Complete Validation Framework: DQ Through PQ

FDA expects pharmaceutical water systems to be validated according to established lifecycle protocols consisting of four sequential phases. Skipping or abbreviating any phase creates regulatory risk and operational vulnerability. Each phase builds on preceding phases, and inadequate execution at any stage compromises system reliability and product safety.

Phase 1: Design Qualification (DQ)

Objective: Document system requirements, design rationale, and intended use before equipment procurement; establish acceptance criteria for subsequent phases.

DQ Deliverables:

- User Requirements Specification (URS): Defines system capacity (gallons/day), quality requirements (microbiological limits, chemical limits), storage requirements, distribution points, temperature setpoints, sanitization approach, hold times, and sampling accessibility

- Functional Requirements: Maps URS requirements to system components (e.g., “Conductivity monitoring required” → specifies sensor type, range, accuracy, calibration frequency)

- Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA): Identifies contamination risks for each system component and establish control measures (e.g., feedwater contamination → mitigated by pretreatment; heat exchanger leakage → mitigated by double tube-sheet design and pressure monitoring)

- Regulatory Requirements Matrix: Traces all FDA 21 CFR 211 and USP <645>/<643> requirements to specific system design elements

- Risk Assessment Document: Assesses risks to products manufactured with system; higher-risk products (parenterals) require more stringent controls

FDA inspectors review DQ documentation to understand design intent. Poorly documented DQ indicates rushed, inadequate planning and typically triggers recommendations for system improvements.

Phase 2: Installation Qualification (IQ)

Objective: Verify that the system is installed according to approved design specifications and engineering drawings.

IQ Verification Activities:

- Design Documentation Review: Verify that P&ID (Process & Instrumentation Diagrams) and equipment drawings match approved DQ and match installed system

- Material Certificate Verification: Confirm all wetted surfaces are 316L stainless steel or approved alternate material; verify material certifications stamped on components

- Welding Records and Surface Finish: Inspect welding records (WPS—Welding Procedure Specification) and verify final surface finish achieved Ra ≤0.6 µm via surface profilometry

- Sensor Calibration and Installation: Calibrate and document all sensors (conductivity probes, thermometers, pressure gauges, pH probes, TOC analyzers) before system startup; verify installation at correct locations

- Dead-Leg Assessment: Measure and document all branch pipe L/D ratios against design specification; identify any dead legs not anticipated in design

- Slope and Drainage Verification: Confirm piping slopes prevent water pooling; verify low points drain completely when circulation stops

- Equipment and Instrumentation Tagging: Verify all equipment has serial numbers, manufacturer identification, and model numbers documented for traceability

Critical Documentation Requirement: Without complete equipment prints and P&ID documentation, systems cannot be considered valid. FDA expects permanent retention of IQ documentation (10+ years). The blog post previously stated “without print will not be considered valid”—this is accurate and critical.

IQ Deliverable: Signed Installation Qualification Report with all verification evidence, photographs of key components, material certificates, welding records, and as-built P&ID reflecting actual installed configuration.

Phase 3: Operational Qualification (OQ)

Objective: Confirm that all system components function correctly under operating conditions and respond appropriately to setpoint changes.

OQ Testing:

- Flow Rate Verification: Measure flow rates at all points of use and main circulation line; verify minimum 0.7 m/s velocity (prevents biofilm formation in recirculation loop)

- Pressure Differentials and Relief Valve Setting: Test pressure differentials across heat exchangers, filters, and piping; confirm relief valve activates at design setpoint

- Temperature Setpoint and Control: Confirm heating system maintains temperature within ±2°C of setpoint; test response to sudden demand or heating system loss

- Conductivity Measurement Accuracy: Validate conductivity measurement using Stage 1, 2, 3 procedure per USP <645> across full operating range

- Vent Filter Integrity: Test vent filter integrity and verify particulate filtration effectiveness; challenge filter with aerosol under maximum system vacuum condition

- Holding Tank Temperature Maintenance: Verify jacketed holding tank maintains setpoint temperature during thermal cycling

- Sanitization System Function: If chemical sanitization is part of design, verify injection rate and distribution throughout system; if thermal sanitization, verify circulation continues during heat-up

- Alarm and Interlock Function: Test temperature alarms (high and low), conductivity alarms, and any interlocks that prevent product use if water quality parameters exceed limits

OQ Deliverable: Operational Qualification Report documenting all system functions tested, acceptance criteria, test results, and photographs of system under operation.

Phase 4: Performance Qualification (PQ)

Objective: Demonstrate that the system consistently produces water meeting specifications under actual manufacturing conditions over extended operation period.

PQ Duration and Phases:

FDA guidance requires minimum 1-year of data. Many facilities structure PQ into three phases:

- Phase 1 (Months 1-3): Intensive monitoring (daily sampling, aggressive environmental monitoring) to establish baseline performance and validate sanitization effectiveness

- Phase 2 (Months 4-9): Routine monitoring with moderate frequency to confirm sustained compliance

- Phase 3 (Months 10-12): Continued routine monitoring at reduced frequency once system demonstrates stability

Alternative structure: Facilities may use 3-month intensive phase followed by 9-month normal operation if early data demonstrates stability.

PQ Sampling Strategy:

| Component | Sample Volume | Minimum Frequency | Parameters Tested | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WFI System Daily | 100-300 mL | Minimum 1 POI (point-of-use) | Conductivity, TOC, microbial, endotoxin | Detect acute contamination |

| WFI System Weekly | 100-300 mL | All POIs | Conductivity, TOC, microbial, endotoxin | Detect chronic contamination patterns |

| Purified Water Daily | 100 mL | Minimum 1 POI | Conductivity, TOC, microbial | Detect acute contamination |

| Purified Water Weekly | 100 mL | Multiple POIs (3-5 locations) | Conductivity, TOC, microbial | Detect chronic patterns, identify dead legs |

| Environmental Monitoring | Ongoing | Daily or weekly | Swab samples of tank surfaces, piping | Detect biofilm or surface contamination |

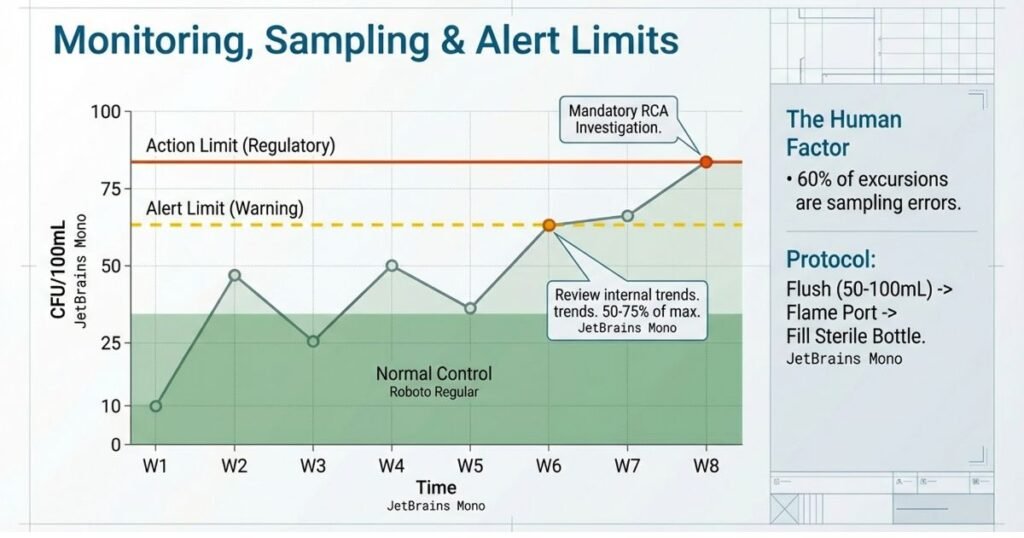

Critical Sampling Error Factor: Sampling errors account for >60% of microbial excursions during PQ. Proper aseptic sampling technique is non-negotiable:

- Flame sample port with 10-15 second Bunsen burner treatment

- First-draw discard: 50-100 mL to purge stagnant water in sample line before collecting test sample

- Use only sterile collection bottles (factory pre-sterilized, not lab-sterilized)

- Immediate testing or proper preservation (refrigeration, fixation per USP requirements)

- Documented training and periodic competency assessment of sampling personnel

Alert and Action Limits Establishment:

Alert limits are warning thresholds (typically 50-75% of action limits) that trigger increased monitoring or investigation. Action limits are decision thresholds that trigger mandatory investigation and product impact assessment.

Recommended WFI Limits:

- Microbial Action Limit: <10 CFU/100 mL (regulatory requirement)

- Microbial Alert Limit: 3-5 CFU/100 mL (facility-specific; adjust based on trending)

- Endotoxin Action Limit: ≤0.25 EU/mL

- Conductivity Alert: Approximately 80% of 1.3 µS/cm (1.0 µS/cm)

- TOC Alert: Approximately 80% of 500 ppb (400 ppb)

Recommended Purified Water Limits:

- Microbial Action Limit: ≤100 CFU/mL (regulatory requirement)

- Microbial Alert Limit: 50-75 CFU/mL (facility-specific; adjust for oral products as needed)

- Conductivity Alert: 1.0-1.1 µS/cm

- TOC Alert: 400 ppb

Trend Analysis and Statistical Process Control:

During PQ, facilities should track:

- 30-day microbial trend (are counts stable, increasing, or decreasing?)

- Seasonal variations (higher microbial counts during summer? Higher conductivity during dry season?)

- Correlation with system events (sanitization, maintenance, personnel changes)

- Point-of-use variations (are some sampling locations consistently higher than others?)

Control charts (X-bar, moving range) help identify trends before excursions occur and support statistical evidence of sustained compliance.

PQ Deliverable: Comprehensive Performance Qualification Report including:

- 1-year (or longer) trend data for all tested parameters

- Alert and action limits established with justification

- Root cause analysis for any excursions

- System release for production use with approved status

- Recommendation for continued monitoring frequency post-validation

Preventing Biofilm Formation in Pharmaceutical Water Systems

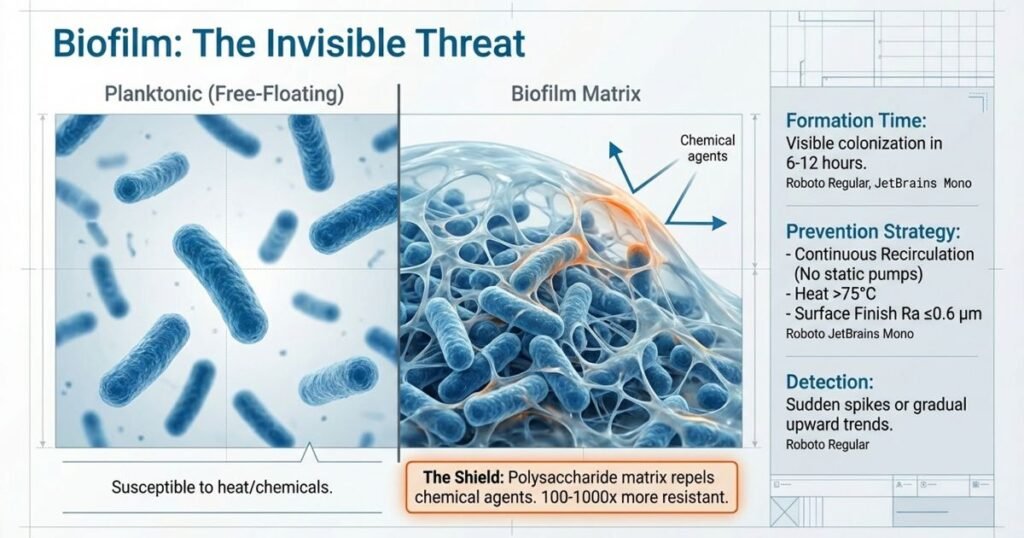

Understanding Biofilm Risk and Formation Mechanism

Biofilms represent the greatest microbiological threat to pharmaceutical water systems. Unlike planktonic (free-floating) bacteria, biofilm bacteria are: resistant to thermal and chemical sanitization (100-1000x more resistant than planktonic cells), difficult to detect via routine microbial sampling (protected by biofilm matrix), and capable of rapid establishment when conditions allow. Once established, biofilms persistently contaminate water systems and trigger repeated excursions of action limits, often leading to system shutdowns and manufacturing interruptions.

Why Biofilms Form More Readily Than Free-Floating Bacteria:

Biofilms are organized microbial communities surrounded by extracellular matrix (polysaccharide, protein, DNA). This matrix protects bacteria from:

- Heat penetration: Biofilms at 80°C show survival rates 100-1000x higher than planktonic cells

- Chemical sanitization: Disinfectant penetration into biofilm slowed by matrix barrier; biofilm interior may never reach killing concentration

- Oxidative stress and nutrient limitation: Biofilm interior is anaerobic, allowing facultative anaerobes to survive

- Antibiotic/antimicrobial exposure: Common sanitizers may not reach effective concentrations within biofilm

Biofilm Formation Timeline:

- Hour 0-6: Initial bacterial attachment to piping surface in low-flow zones

- Hour 6-12: Initial colonization becomes visible under microscope; extracellular matrix begins forming

- Hour 12-24: Established biofilm with multiple cell layers; beginning to show resistance to sanitization

- Day 2-5: Mature biofilm resistant to thermal and chemical treatment; capable of planktonic shedding under stress

This accelerated timeline (visible biofilm within 6-12 hours) explains why low-flow dead zones and stagnant pump reservoirs become persistently contaminated. Once biofilm establishes, removing it requires aggressive intervention beyond routine sanitization.

Biofilm Prevention Through Design and Operation

Design Principle 1: Maintain Flow Velocity ≥0.7 m/s

Biofilm attachment requires low-flow conditions. Piping and circulation system design must maintain minimum velocity of 0.7 m/s (meters per second) throughout all recirculation loops. This velocity is sufficient to prevent bacterial settlement and biofilm initiation.

Velocity calculation: V = Q / A, where:

- V = velocity (m/s)

- Q = volumetric flow rate (m³/s)

- A = cross-sectional area of pipe (m²)

For 1-inch diameter stainless steel tubing circulating 2 gallons per minute (0.126 L/s = 0.000126 m³/s):

- Internal diameter = 25.4 mm = 0.0254 m

- Cross-sectional area = π(0.0127)² = 5.07 × 10⁻⁴ m²

- Velocity = 0.000126 / (5.07 × 10⁻⁴) = 0.25 m/s ← Below 0.7 m/s; biofilm risk HIGH

Increasing flow to 5.6 GPM achieves approximately 0.7 m/s velocity and adequate biofilm prevention.

Design Principle 2: Eliminate or Minimize Dead Legs

Dead legs are stagnant branch pipes where water cannot circulate effectively. Each dead leg is a biofilm reservoir:

- Stagnant water accumulates; temperature drops in dead legs due to no circulation and ambient cooling

- Nutrients concentrate at low-velocity zones (bacteria utilize residual organics from system materials)

- Thermal sanitization penetrates poorly into dead legs compared to main circulation

- Chemical sanitization has limited effectiveness in stagnant pockets

- Each dead leg is independently vulnerable; multiple dead legs create distributed biofilm sources

Modern Design Standard: Eliminate all dead legs where possible. When unavoidable, design to ≤1.5D (length-to-diameter ratio). For less critical applications (purified water systems), ≤3D is acceptable if enhanced monitoring compensates.

Design Principle 3: Smooth Piping Interior and Low Surface Area

Rough surfaces (Ra >0.6 µm) promote biofilm attachment and increase surface area available for microbial colonization:

- Electropolished 316L stainless steel (Ra ≤0.6 µm) strongly resists biofilm attachment

- Avoid carbon steel, unpolished stainless, or rough surface coatings

- Hygienic fittings (flush-mounted, low-profile valve connections) minimize dead space and reduce total biofilm surface area

Even small surface defects (corrosion pits, scratches, deposits) serve as biofilm initiation sites.

Design Principle 4: Continuous Recirculation

Systems that maintain continuous water circulation prevent biofilm formation through persistent hydrodynamic stress. Intermittent pump operation significantly increases biofilm risk:

- Continuous circulation at ≥0.7 m/s prevents bacterial settlement throughout system

- Intermittent operation (e.g., pumps running only during production hours) allows bacterial settlement during idle periods

- Temperature maintenance during idle periods critical: cold (ambient temperature) systems are ideal biofilm environments

Facilities utilizing systems with intermittent operation should: (1) Maintain elevated temperature even during idle periods, (2) increase microbial sampling frequency to 2-3× normal, (3) consider periodic chemical sanitization, (4) implement environmental monitoring (swab sampling) to detect biofilm presence.

Design Principle 5: Temperature Maintenance and Monitoring

Temperature fluctuations increase biofilm formation risk:

- Maintain ≥75°C for hot WFI systems to ensure self-sanitization

- Temperature setpoint dips to 70°C increase microbial recovery; dips below 65°C allow biofilm development

- Uninsulated piping or failed heating systems are common causes of temperature fluctuation

- System must recover to 80°C within 2-4 hours of any temperature excursion

Temperature monitoring with high and low alarms is essential; alarms should alert operations when temperature dips below 70°C or rises above 85°C (indicating heating system malfunction).

Biofilm Prevention Through Sanitization Strategy

Thermal Sanitization (Preferred):

- Continuous thermal sanitization: Regular operation at 80°C continuously (hot circulating systems) provides ongoing biofilm suppression through heat stress on microbial cells

- Periodic heat treatment: For cold systems or systems with intermittent operation, scheduled heating events (e.g., weekly 80°C circulation for 2-4 hours) provides biofilm control

- Validated time-temperature combinations: Historical industry data and regulatory guidance support that 80°C continuous operation eliminates biofilm. Shorter-duration heat treatments (e.g., 85°C for 1 hour) can achieve biofilm control if heating is insufficient in other areas.

Most pharmaceutical facilities prefer thermal sanitization because it requires minimal operator intervention, leaves no chemical residues, and aligns naturally with hot water system design.

Chemical Sanitization:

- Ozone treatment (3-5 ppm in storage tanks, 30-60 minutes contact time): Bactericidal without residues; degrades to oxygen; approved by FDA

- Hot water with citric acid (0.1-1% citric acid at 60-80°C for 2-4 hours): Effective biofilm disruption; citric acid is acidic (pH 2-3) and disrupts biofilm matrix; rinse thoroughly post-treatment

- Sodium hydroxide (0.1-1 N NaOH, 2-4 hours room temperature): Disrupts biofilm matrix through alkaline saponification; requires thorough rinsing

- Other approved sanitants: Peracetic acid (0.02-0.2%), hydrogen peroxide (3-10%) per facility-specific validation

Chemical sanitization frequency depends on risk assessment: systems with good design (minimal dead legs, high flow velocity, high temperature) may require quarterly sanitization; systems with design compromises may require monthly sanitization.

Mechanical Cleaning:

- Piping flushing with high-velocity water or compressed air to physically dislodge biofilm

- Pipe swabbing in suspect areas using sterile sampling swabs followed by culture analysis

- Clean-in-Place (CIP) systems for RO membranes and complex equipment using automated chemical circulation and temperature control

Biofilm Detection and Monitoring

Routine Environmental Monitoring:

- Daily or weekly microbial sampling from at-risk points of use, low-velocity zones, dead legs, and stagnant areas

- Sudden increases in microbial counts (5-10 CFU/mL jumps from <1 CFU/mL baseline) suggest biofilm shedding

- Trend analysis: if microbial counts gradually increase over days/weeks despite sanitization, biofilm may be developing

Biofilm-Specific Testing:

- Swab sampling of internal pipe surfaces (destructive testing; piping must be cut open) followed by culture and identification

- ATP (Adenosine Triphosphate) bioluminescence testing for rapid ATP (cell energy molecule) detection; correlates with biofilm presence

- Dye injection tests using fluorescent tracers to identify stagnant zones where biofilm is likely developing

- DNA-based microbial identification (qPCR, next-generation sequencing) when specific contamination detected; identifies organism type and source

Response to Biofilm Detection:

- Investigate immediately; do not continue production use with confirmed or suspected biofilm

- Increase sanitization frequency and intensity (daily or multiple-daily heat treatment)

- Consider temporary process water use from approved alternate source

- Perform root cause analysis: flow velocity problem? Temperature drop? Dead leg? Pump stagnation?

- After remediation, validate system cleanliness before resuming production (e.g., 7-day biofilm-free period at ≤1 CFU/100 mL for WFI)

Regulatory Compliance and Documentation Requirements

FDA Regulatory Framework

Primary Regulatory References:

The FDA expects pharmaceutical facilities to maintain pharmaceutical water systems in compliance with:

- 21 CFR 211.113: Requirements for water used in drug manufacturing; requires water used in formulation to meet specified chemical, physical, and microbial specifications

- 21 CFR 211.160: Environmental monitoring and testing requirements; mandates periodic testing of water systems and corrective action protocols when specifications exceeded

- FDA Guide to Inspections of High Purity Water Systems (July 1993): This guidance, though published in 1993, remains actively used by FDA inspectors during routine facility inspections. While some elements are dated (6D dead-leg rule), the document comprehensively addresses FDA expectations for system design, validation, and control.

FDA Inspection Triggers and Common Findings:

FDA inspections of water systems often identify:

- Inadequate Design Qualification documentation

- Dead-leg violation (measurements exceed approved standard or no measurements documented)

- Inadequate validation data (PQ less than 1 year, insufficient sampling points)

- Biofilm contamination or unexplained microbial excursions without documented investigation

- Vent filter integrity testing not performed or documented

- Temperature excursions not detected or documented

- Corrective action delays (FDA expects investigation within 24-48 hours of out-of-spec result)

USP and Compendial Standards

| USP Chapter | Topic | Regulatory Status | Key Guidance |

|---|---|---|---|

| USP <1231> | Water for Pharmaceutical Purposes | Mandatory reference | Defines water categories, specifications, USP references, usage requirements |

| USP <645> | Water Conductivity Testing | Mandatory reference | Three-stage conductivity measurement procedure; acceptance ranges |

| USP <643> | Total Organic Carbon (TOC) Testing | Mandatory reference | TOC analysis methodology and validation procedures |

| USP <85> | Bacterial Endotoxins Test (LAL) | Mandatory reference | Limulus Amebocyte Lysate test procedures, equipment qualification, control standard |

| USP <2> | General Notices | Regulatory reference | Defines allowable water types for drug substance synthesis and formulation |

USP monographs are incorporated by reference into FDA regulations. Compliance with USP standards is therefore mandatory for FDA compliance. Facilities must maintain current USP references; the FDA does not recognize outdated USP versions.

Documentation Requirements for Regulatory Compliance

Comprehensive documentation is essential for FDA compliance and system validation. Minimum required documentation includes:

Validation Phase Documentation:

- Design Qualification Report: URS, design rationale, risk assessment, FMEA, regulatory requirements matrix

- Installation Qualification Report: Material certificates, calibration records, equipment verification, photographs, as-built P&ID

- Operational Qualification Report: Functionality testing results, system response documentation, acceptance criteria verification

- Performance Qualification Report: 1-year trend data, alert/action limits, deviation investigation outcomes, system release authorization

Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs):

- System operation (startup, operation, shutdown procedures)

- Sanitization procedures (thermal or chemical; frequency, duration, acceptance criteria)

- Sampling procedures (technique, frequency, documentation, error prevention)

- Monitoring procedures (real-time monitoring, alert/alarm response)

- Deviation response procedures (investigation timeline, documentation, escalation)

- Maintenance and calibration procedures (sensor calibration, vent filter integrity testing, equipment inspection)

- Change control procedures (for any system modifications affecting validation)

Ongoing Records:

- Daily or weekly monitoring records (microbial, conductivity, TOC, endotoxin results)

- Sampling logs with dates, times, personnel names, results, and acceptance decisions

- Equipment calibration certificates and maintenance logs (serial numbers, dates, personnel)

- Environmental monitoring records (swabs, ATP testing if used)

- Deviation investigations and corrective action documentation

- Change control records for any system modifications with validation re-assessment

Documentation Retention: FDA expects permanent retention of validation documentation and baseline monitoring records; minimum 10 years for manufacturing records per 21 CFR 211.180. Consider maintaining indefinitely for regulatory inspection readiness and product liability protection.

Frequently Asked Questions:

-

What is the difference between Water for Injection (WFI) and Purified Water?

Water for Injection is the highest-purity water grade, required for parenteral (injectable) products, biologics, and sterile formulations. WFI must meet stricter limits: <10 CFU/100 mL microbial contamination and ≤0.25 EU/mL endotoxins (pyrogens). Purified Water is used for non-sterile products (tablets, oral liquids, topical products) and allows up to ≤100 CFU/mL microbial contamination. Both are typically produced through distillation or RO-EDI, but WFI requires additional endotoxin removal validation. The key difference is pyrogen (endotoxin) control: parenteral products must eliminate fever-causing bacterial endotoxins, while non-sterile products do not require this level of endotoxin control.

-

Why must both endotoxin (LAL) and microbial testing be performed for WFI?

WFI can pass the LAL endotoxin test but fail microbial limits. This occurs because the LAL test uses only 0.1 mL sample volume, while microbial testing uses 100 mL. The larger sample volume makes microbial testing a more sensitive indicator of system contamination and biofilm presence. Additionally, endotoxins are heat-stable molecules that persist even after bacteria are killed, so endotoxin levels don’t always correlate with viable microbial counts. Best practice performs both tests to ensure complete system assessment: endotoxin testing confirms feedwater quality and WFI production effectiveness, while microbial testing confirms system cleanliness and absence of biofilm.

-

Why is temperature so critical in pharmaceutical water systems?

Temperature maintains system cleanliness through two mechanisms: (1) Self-sanitization: At ≥75°C, elevated temperature creates stress conditions that suppress biofilm growth and kill planktonic microorganisms. Continuous operation at 80°C prevents biofilm establishment. (2) Stagnation prevention: Continuous circulation at elevated temperature prevents low-flow dead zones where biofilm readily forms. Even brief temperature fluctuations from 80°C to 70°C increase microbial recovery risk and trigger biofilm development. Temperature excursions are among the most common causes of unexplained microbial contamination in otherwise well-designed systems.

-

How often should pharmaceutical water systems be microbially sampled?

FDA guidance recommends minimum daily sampling from at least one point-of-use for WFI and purified water systems, with all points tested weekly. During Performance Qualification (PQ validation phase), intensive sampling (daily at all points) establishes baseline contamination profile. After PQ completion, facilities may reduce to approved maintenance frequency if data demonstrates stability and system design is robust. High-risk systems or systems with history of excursions may require increased frequency (multiple daily points or twice-weekly testing). Sampling frequency should be justified in the system’s operating procedures based on risk assessment.

-

What is a pharmaceutical water system “dead leg” and why is it problematic?

A dead leg is a stagnant branch pipe where water cannot circulate effectively, creating a low-flow zone where bacteria easily settle and biofilm readily forms. Dead legs are problematic because: (1) Stagnant water accumulates, providing time for microbial growth; (2) Temperature drops in dead legs due to no circulation and ambient cooling; (3) Thermal sanitization penetrates poorly into dead legs; (4) Chemical sanitization is less effective in stagnant zones; (5) Each dead leg is independently vulnerable to biofilm formation. Modern design standards limit dead legs to ≤3D (length-to-diameter ratio) for standard applications, with ≤1.5D preferred for critical WFI systems. Dead-leg-free design is the ideal but not always feasible.

-

Can RO-EDI (Reverse Osmosis with Electrodeionization) systems be used to produce FDA-compliant WFI?

Yes, RO-EDI systems are now widely accepted by FDA and EMA for WFI production when rigorous validation proves equivalence to distillation. RO-EDI advantages include energy efficiency, faster production, and scalability for high-volume applications. However, proper design is critical: RO systems must include series-configured membranes (two in sequence for redundancy), UV pretreatment to reduce microbial load, heat exchangers to maintain elevated temperature (75-80°C), and post-RO hot circulation or sanitization. Distillation stills typically guarantee ≥2.5-3 log endotoxin reduction; RO-EDI systems must achieve equivalent performance through appropriate design and validation.

-

What should a facility do if a water system exceeds action limits?

According to FDA policy, action limits are not “pass/fail” thresholds. When an action limit is exceeded, the facility must: (1) Immediately stop using water from the affected system for production; (2) Initiate investigation within 24-48 hours documenting probable cause; (3) Implement corrective actions (increased sanitization, equipment repair, feedwater improvement); (4) Perform impact assessment on all products manufactured since last compliant result; (5) Document all findings and corrective actions; (6) Retest to confirm water quality has returned to compliant state; (7) Assess if product batches require review or recall. FDA expects thorough investigation even for single excursions; repeated excursions without identified root cause trigger regulatory concern and may result in inspection findings.

-

What documentation must be maintained for FDA inspection readiness?

FDA expects permanent retention of: (1) Complete validation package (DQ, IQ, OQ, PQ) with all supporting evidence; (2) SOPs for system operation, sanitization, sampling, and deviation response; (3) Calibration certificates and maintenance records for all instrumentation; (4) Routine monitoring records (daily/weekly results, trends, alert/action limit tracking); (5) Deviation investigations and corrective action documentation; (6) Change control records for any system modifications; (7) Environmental monitoring data; (8) Training records for personnel involved in system operation and sampling. Minimum retention is 10 years per FDA regulations; consider indefinite retention for critical systems. All records should be organized for easy retrieval during inspection.

References:

- FDA Guide to Inspections of High Purity Water Systems (July 1993). U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Inspection Guides. Available: https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/inspection-guides/high-purity-water-system-79

- FDA 21 CFR Part 211 – Current Good Manufacturing Practice for Finished Pharmaceuticals. U.S. Code of Federal Regulations, Title 21, Part 211. Available: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/part-211

- FDA 21 CFR 211.113 & 211.160 – Water and Environmental Monitoring Requirements. U.S. Code of Federal Regulations, Title 21, Sections 211.113 and 211.160.

- USP <1231> Water for Pharmaceutical Purposes. United States Pharmacopeia, The National Formulary (USP-NF). Pharmacopeial Convention, Rockville, MD.

- Pharmaceutical Water Validation: A Practical and Regulatory-Focused Guide in Year 2026 (2025). Pharmuni, December 2025. Available: https://pharmuni.com/pharmaceutical-water-validation/

- USP <645> Water Conductivity Testing and Measurement. United States Pharmacopeia Standards, Monograph <645>. Electrodeionization and conductivity measurement procedures for pharmaceutical water systems.

- WFI System: The Complete FAQ Guide In 2025 (2025). AIPAK Engineering, October 2025. Available: https://aipakengineering.com/wfi-system/

- USP <85> Bacterial Endotoxins Test (Limulus Amebocyte Lysate Method). United States Pharmacopeia Standards, Monograph <85>. Procedures for LAL testing and pyrogen limit verification.

- Purified Water System Validation: Steps, Phases and Compliance Guide (2025). Pharmaguideline, December 2025. Available: https://www.pharmaguideline.com/purified-water-system-validation.html

- Pharmaceutical Water Systemvalidation Aspects (2024). Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research, Review Article. Available: https://www.jocpr.com/articles/pharmaceutical-water-system-validation-aspects.pdf

- Validate a Water System for FDA and USP Compliance (2025). PureTec Water, June 2025. Available: https://puretecwater.com/resources/validate-a-water-system-for-fda-and-usp-compliance/

- Water for Injection (WFI) System Validation in Pharmaceutical Manufacturing (2025). Pharmaguideline, December 2025. Available: https://www.pharmaguideline.com/2013/01/water-for-injection-wfi-system.html

- Validation Methods for Water Systems of Pharmaceutical Use (2024). International Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Analysis, July 2024. Available: https://www.ijcpa.in/articles/validation-methods-for-water-systems-of-pharmaceutical-use.pdf

- High Purity Water System (FDA Inspection Guide 7/93) (2016). FDA Inspections Compliance Enforcement and Criminal Investigations, September 2016. Technical guidance on water system design, validation, and FDA compliance expectations.

- Biofilm Formation in Water Systems: Detection, Control and Remediation (2023). Pharma GMP, Regulatory Article. Available: https://www.pharmagmp.in/biofilm-formation-in-water-systems-detection-control-and-remediation/

- Prevention and Control of Biofilms in Pharmaceutical Water Systems (2024). LinkedIn Pulse, July 2024. Professional guidance on biofilm prevention strategy and control mechanisms.

- Reverse Osmosis Systems for Pharmaceutical Water Production: Technical Considerations (2024). Mabion, Risk Management Strategies for Biofilms in Water Systems. Available: https://www.mabion.eu/science-hub/articles/risk-management-biofilms-water-systems/

- Dead Leg and Its Limit in Water Systems (2014). Pharmaguideline, January 2014. Technical reference for dead-leg design standards, L/D ratios, and acceptable limits.

- Dead Legs in Piping Systems – Hygienic Design! (2025). LinkedIn Pulse, Alan Friis, March 2025. Professional guidance on dead-leg measurement, current standards (1.5D, 3D, 6D), and design best practices.

- Water for Pharmaceutical Use – Technical Standards (2014). FDA Inspections Compliance Enforcement and Criminal Investigations, August 2014. Guidance on water specifications, testing requirements, and validation protocols.

- Pharmaceutical Water Validation: Tests & 2026 Guidelines (2025). Pharmuni, December 2025. Current pharmaceutical water validation requirements, sampling strategies, and 2026 regulatory updates.

- Performance Qualification Phase Documentation and Execution (2024). Pharma Industry Standards, Technical Guide. Requirements for PQ sampling, frequency, statistical analysis, and deviation investigation.

- The Problem of Biofilms and Pharmaceutical Water Systems (2020). American Pharmaceutical Review, Featured Article, January 2020. Comprehensive review of biofilm formation mechanisms, detection methods, and control strategies.

- Risk Management Strategies for Biofilms in Water Systems Used in Sterile Drug Manufacturing (2025). Mabion, December 2025. Advanced biofilm risk mitigation, detection technologies, and remediation approaches.

- FDA Form 483 & Warning Letters – Water System Deficiencies (2023-2025). FDA Enforcement Reports. Analysis of common water system findings during FDA inspections, including documentation gaps, validation inadequacies, and biofilm-related violations.